- 📝 Posted:

- 🚚 Summary of:

- P0264, P0265

- ⌨ Commits:

46cd6e7...78728f6,78728f6...ff19bed- 💰 Funded by:

- Blue Bolt, [Anonymous], iruleatgames

- 🏷 Tags:

Oh, it's 2024 already and I didn't even have a delivery for December or January? Yeah… I can only repeat what I said at the end of November, although the finish line is actually in sight now. With 10 pushes across 4 repositories and a blog post that has already reached a word count of 9,240, the Shuusou Gyoku SC-88Pro BGM release is going to break 📝 both the push record set by TH01 Sariel two years ago, and 📝 the blog post length record set by the last Shuusou Gyoku delivery. Until that's done though, let's clear some more PC-98 Touhou pushes out of the backlog, and continue the preparation work for the non-ASCII translation project starting later this year.

But first, we got another free bugfix according to my policy! 📝 Back in April 2022 when I researched the Divide Error crash that can occur in TH04's Stage 4 Marisa fight, I proposed and implemented four possible workarounds and let the community pick one of them for the generally recommended small bugfix mod. I still pushed the others onto individual branches in case the gameplay community ever wants to look more closely into them and maybe pick a different one… except that I accidentally pushed the wrong code for the warp workaround, probably because I got confused with the second warp variant I developed later on.

Fortunately, I still had the intended code for both variants lying around, and used the occasion to merge the current master branch into all of these mod branches. Thanks to wyatt8740 for spotting and reporting this oversight!

- The Music Room background masking effect

- The GRCG's plane disabling flags

- Text color restrictions

- The entire messy rest of the Music Room code

- TH04's partially consistent congratulation picture on Easy Mode

- TH02's boss position and damage variables

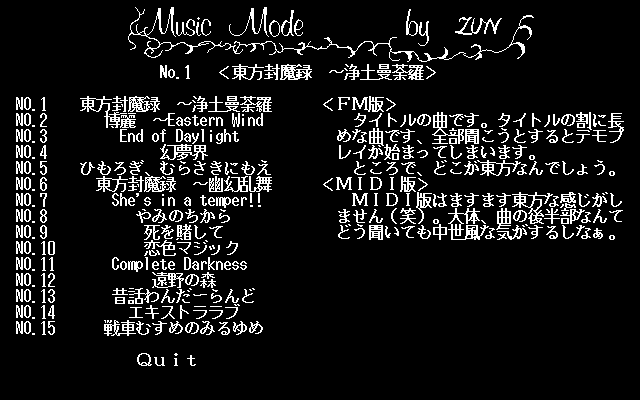

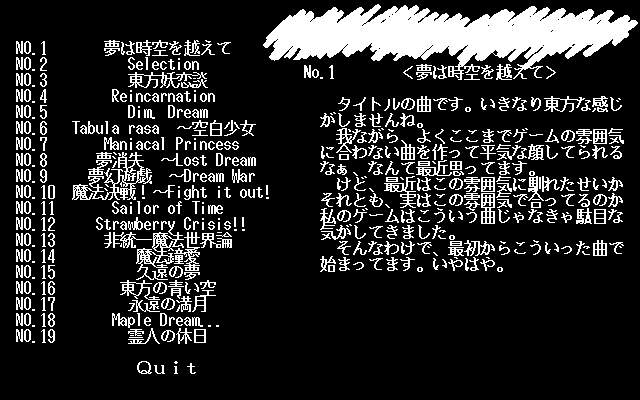

As the final piece of code shared in largely identical form between 4 of the 5 games, the Music Rooms were the biggest remaining piece of low-hanging fruit that guaranteed big finalization% gains for comparatively little effort. They seemed to be especially easy because I already decompiled TH02's Music Room together with the rest of that game's OP.EXE back in early 2015, when this project focused on just raw decompilation with little to no research. 9 years of increased standards later though, it turns out that I missed a lot of details, and ended up renaming most variables and functions. Combined with larger-than-expected changes in later games and the usual quality level of ZUN's menu code, this ended up taking noticeably longer than the single push I expected.

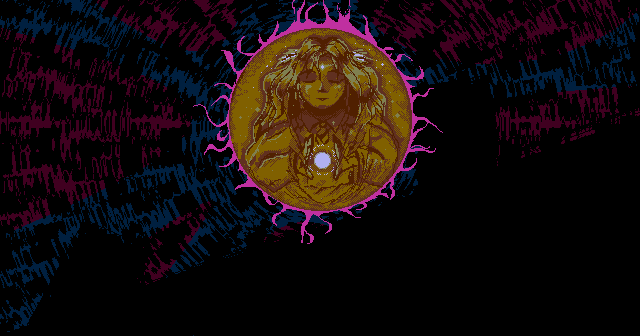

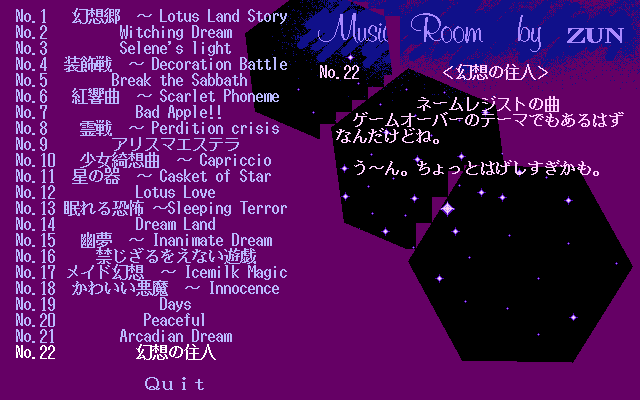

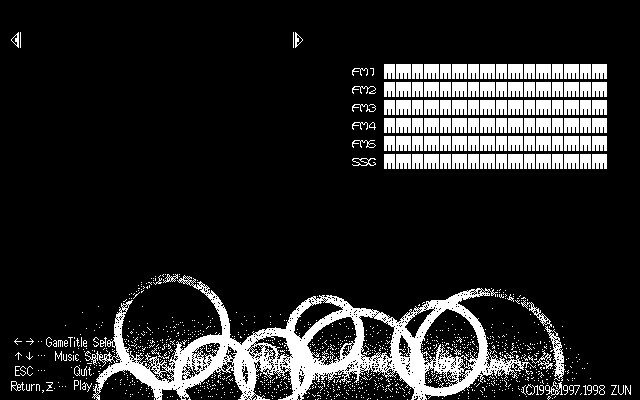

The undoubtedly most interesting part about this screen is the animation in the background, with the spinning and falling polygons cutting into a single-color background to reveal a spacey image below. However, the only background image loaded in the Music Room is OP3.PI (TH02/TH03) or MUSIC3.PI (TH04/TH05), which looks like this in a .PI viewer or when converted into another image format with the usual tools:

That is definitely the color that appears on top of the polygons, but where is the spacey background? If there is no other .PI file where it could come from, it has to be somewhere in that same file, right? ![]()

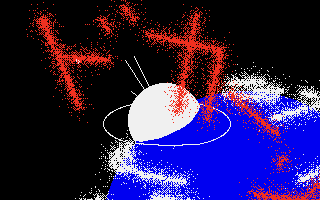

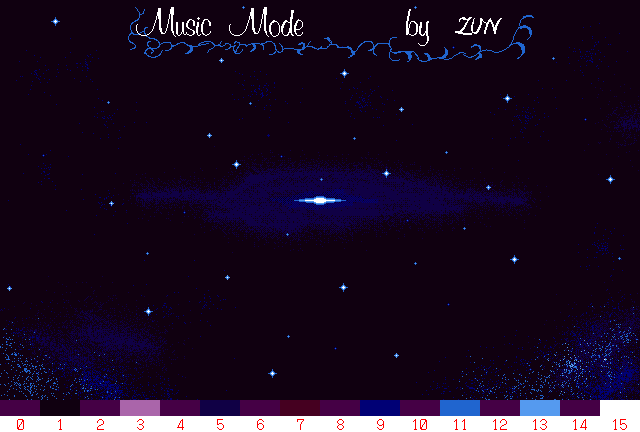

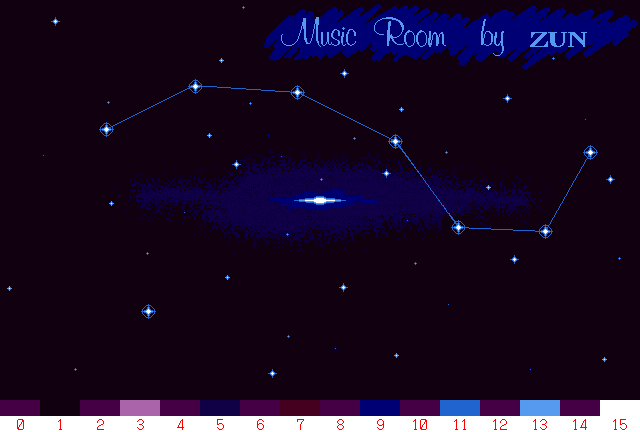

And indeed: This effect is another bitplane/color palette trick, exactly like the 📝 three falling stars in the background of TH04's Stage 5. If we set every bit on the first bitplane and thus change any of the resulting even hardware palette color indices to odd ones, we reveal a full second 8-color sub-image hiding in the same .PI file:

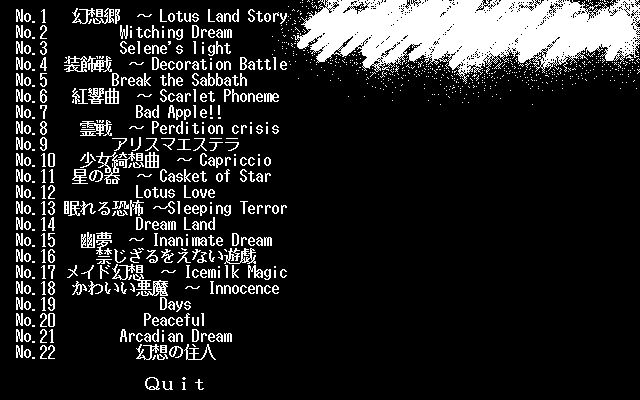

On a high level, the first bitplane therefore acts as a stencil buffer that selects between the blank and spacey sub-image for every pixel. The important part here, however, is that the first bitplane of the blank sub-images does not consist entirely of 0 bits, but does have 1 bits at the pixels that represent the caption that's supposed to be overlaid on top of the animation. Since there now are some pixels that should always be taken from the spacey sub-image regardless of whether they're covered by a polygon, the game can no longer just clear the first bitplane at the start of every frame. Instead, it has to keep a separate copy of the first bitplane's original state (called nopoly_B in the code), captured right after it blitted the .PI image to VRAM. Turns out that this copy also comes in quite handy with the text, but more on that later.

Then, the game simply draws polygons onto only the reblitted first bitplane to conditionally set the respective bits. ZUN used master.lib's grcg_polygon_c() function for this, which means that we can entirely thank the uncredited master.lib developers for this iconic animation – if they hadn't included such a function, the Music Rooms would most certainly look completely different.

This is where we get to complete the series on the PC-98 GRCG chip with the last remaining four bits of its mode register. So far, we only needed the highest bit (0x80) to either activate or deactivate it, and the bit below (0x40) to choose between the 📝 RMW and 📝 TCR/📝 TDW modes. But you can also use the lowest four bits to restrict the GRCG's operations to any subset of the four bitplanes, leaving the other ones untouched:

// Enable the GRCG (0x80) in regular RMW mode (0x40). All bitplanes are // enabled and written according to the contents of the tile register. outportb(0x7C, 0xC0); // The same, but limiting writes to the first bitplane by disabling the // second (0x02), third (0x04), and fourth (0x08) one, as done in the // PC-98 Touhou Music Rooms. outportb(0x7C, 0xCE); // Regular GRCG blitting code to any VRAM segment… pokeb(0xA8000, offset, …); // We're done, turn off the GRCG. outportb(0x7C, 0x00);

This could be used for some unusual effects when writing to two or three of the four planes, but it seems rather pointless for this specific case at first. If we only want to write to a single plane, why not just do so directly, without the GRCG? Using that chip only involves more hardware and is therefore slower by definition, and the blitting code would be the same, right?

This is another one of these questions that would be interesting to benchmark one day, but in this case, the reason is purely practical: All of master.lib's polygon drawing functions expect the GRCG to be running in RMW mode. They write their pixels as bitmasks where 1 and 0 represent pixels that should or should not change, and leave it to the GRCG to combine these masks with its tile register and OR the result into the bitplanes instead of doing so themselves. Since GRCG writes are done via MOV instructions, not using the GRCG would turn these bitmasks into actual dot patterns, overwriting any previous contents of each VRAM byte that gets modified.

Technically, you'd only have to replace a few MOV instructions with OR to build a non-GRCG version of such a function, but why would you do that if you haven't measured polygon drawing to be an actual bottleneck.

As far as complexity is concerned though, the worst part is the implicit logic that allows all this text to show up on top of the polygons in the first place. If every single piece of text is only rendered a single time, how can it appear on top of the polygons if those are drawn every frame?

Depending on the game (because of course it's game-specific), the answer involves either the individual bits of the text color index or the actual contents of the palette:

- Colors 0 or 1 can't be used, because those don't include any of the bits that can stay constant between frames.

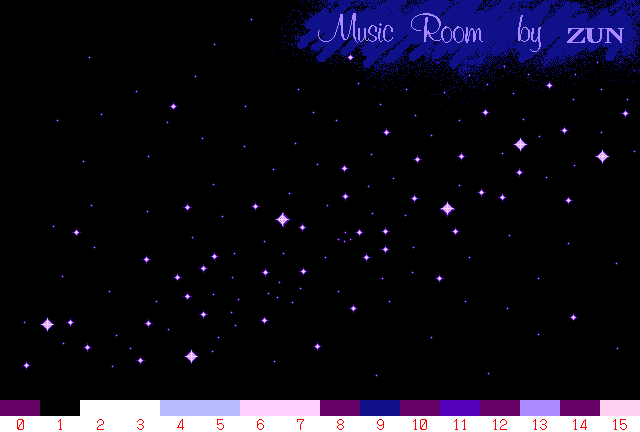

- If the lowest bit of a palette color index has no effect on the displayed color, text drawn in either of the two colors won't be visually affected by the polygon animation and will always appear on top. TH04 and TH05 rely on this property with their colors 2/3, 4/5, and 6/7 being identical, but this would work in TH02 and TH03 as well.

- But this doesn't apply to TH02 and TH03's palettes, so how do they do it? The secret: They simply include all text pixels in

nopoly_B. This allows text to use any color with an odd palette index – the lowest bit then won't be affected by the polygonsORed into the first bitplane, and the other bitplanes remain unchanged. - TH04 is a curious case. Ostensibly, it seems to remove support for odd text colors, probably because the new 10-frame fade-in animation on the comment text would require at least the comment area in VRAM to be captured into

nopoly_Bon every one of the 10 frames. However, the initial pixels of the tracklist are still included innopoly_B, which would allow those to still use any odd color in this game. ZUN only removed those fromnopoly_Bin TH05, where it had to be changed because that game lets you scroll and browse through multiple tracklists.

nopoly_B with each game's first track selected.Finally, here's a list of all the smaller details that turn the Music Rooms into such a mess:

Due to the polygon animation, the Music Room is one of the few double-buffered menus in PC-98 Touhou, rendering to both VRAM pages on alternate frames instead of using the other page to store a background image. Unfortunately though, this doesn't actually translate to tearing-free rendering because ZUN's initial implementation for TH02 mixed up the order of the required operations. You're supposed to first wait for the GDC's VSync interrupt and then, within the display's vertical blanking interval, write to the relevant I/O ports to flip the accessed and shown pages. Doing it the other way around and flipping as soon as you're finished with the last draw call of a frame means that you'll very likely hit a point where the (real or emulated) electron beam is still traveling across the screen. This ensures that there will be a tearing line somewhere on the screen on all but the fastest PC-98 models that can render an entire frame of the Music Room completely within the vertical blanking interval, causing the very issue that double-buffering was supposed to prevent.

ZUN only fixed this landmine in TH05.The polygons have a fixed vertex count and radius depending on their index, everything else is randomized. They are also never reinitialized while

OP.EXEis running – if you leave the Music Room and reenter it, they will continue animating from the same position.Except for TH05's repeatable ⬆️ up and ⬇️ down inputs, the games force you to release any pressed key before they will handle any new input. But since the game is running on a PC-98, we 📝 once again have to mention the infamous quirk of the keyboard controller with regard to held keys. Funnily enough, the games go back and forth in how they address it, in a way that matches the 📝 additional delay of the cutscene interpreter loop:

- TH02 and TH04 don't handle it at all, causing held keys to be processed again after about a second.

- TH03 and TH05 correctly work around the quirk, at the usual cost of a 614.4 µs delay per frame. Except that the delay is actually twice as long in frames in which a previously held key is released, because this code is a mess.

But even in 2024, DOSBox-X is the only emulator that actually replicates this detail of real hardware. On anything else, keyboard input will behave as ZUN intended it to. At least I've now mentioned this once for every game, and can just link back to this blog post for the other menus we still have to go through, in case their game-specific behavior matches this one.

TH02 is the only game that

- separately lists the stage and boss themes of the main game, rather than following the in-game order of appearance,

- continues playing the selected track when leaving the Music Room,

- always loads both MIDI and PMD versions, regardless of the currently selected mode, and

- does not stop the currently playing track before loading the new one into the PMD and MMD drivers.

The combination of 2) and 3) allows you to leave the Music Room and change the music mode in the Option menu to listen to the same track in the other version, without the game changing back to the title screen theme. 4), however, might cause the PMD and MMD drivers to play garbage for a short while if the music data is loaded from a slow storage device that takes longer than a single period of the OPN timer to fill the driver's song buffer. Probably not worth mentioning anymore though, now that people no longer try fitting PC-98 Touhou games on floppy disks.

The comment text files use another fixed-size plaintext format, just like 📝 TH02's in-game dialog system or 📝 TH03's win messages:

- Exactly 40 (TH02/TH03) / 38 (TH04/TH05) visible bytes per line,

- padded with 2 bytes that can hold a CR/LF newline sequence for easier editing.

- Every track starts with a title line that mostly just duplicates the names from the hardcoded tracklist,

- followed by a fixed 19 (TH02/TH03/TH04) / 9 (TH05) comment lines.

In TH04 and TH05, lines can start with a semicolon (

;) to prevent them from being rendered. This is purely a performance hint, and is visually equivalent to filling the line with spaces.All in all, the quality of the code is even slightly below the already poor standard for PC-98 Touhou: More VRAM page copies than necessary, conditional logic that is nested way too deeply, a distinct avoidance of state in favor of loops within loops, and – of course – a couple of

gotos to jump around as needed.

In TH05, this gets so bad with the scrolling and game-changing tracklist that it all gives birth to a wonderfully obscure inconsistency: When pressing both ⬆️/⬇️ and ⬅️/➡️ at the same time, the game first processes the vertical input and then the horizontal one in the next frame, making it appear as if the latter takes precedence. Except when the cursor is highlighting the first (⬆️ ) or 12th (⬇️ ) element of the list, and said list element is not the first track (⬆️ ) or the quit option (⬇️ ), in which case the horizontal input is ignored.

And that's all the Music Rooms! The OP.EXE binaries of TH04 and especially TH05 are now very close to being 100% RE'd, with only the respective High Score menus and TH04's title animation still missing. As for actual completion though, the finalization% metric is more relevant as it also includes the ZUN Soft logo, which I RE'd on paper but haven't decompiled. I'm 📝 still hoping that this will be the final piece of code I decompile for these two games, and that no one pays to get it done earlier… ![]()

For the rest of the second push, there was a specific goal I wanted to reach for the remaining anything budget, which was blocked by a few functions at the beginning of TH04's and TH05's MAINE.EXE. In another anticlimactic development, this involved yet another way too early decompilation of a main() function…

Generally, this main() function just calls the top-level functions of all other ending-related screens in sequence, but it also handles the TH04-exclusive congratulating All Clear

images within itself. After a 1CC, these are an additional reward on top of the Good Ending, showing the player character wearing a different outfit depending on the selected difficulty. On Easy Mode, however, the Good Ending is unattainable because the game always ends after Stage 5 with a Bad Ending, but ZUN still chose to show the EASY ALL CLEAR!!

image in this case, regardless of how many continues you used.

While this might seem inconsistent with the other difficulties, it is consistent within Easy Mode itself, as the enforced Bad Ending after Stage 5 also doesn't distinguish between the number of continues. Also, Try to Normal Rank!!

could very well be ZUN's roundabout way of implying "because this is how you avoid the Bad Ending".

With that out of the way, I was finally able to separate the VRAM text renderer of TH04 and TH05 into its own assembly unit, 📝 finishing the technical debt repayment project that I couldn't complete in 2021 due to assembly-time code segment label arithmetic in the data segment. This now allows me to translate this undecompilable self-modifying mess of ASM into C++ for the non-ASCII translation project, and thus unify the text renderers of all games and enhance them with support for Unicode characters loaded from a bitmap font. As the final finalized function in the SHARED segment, it also allowed me to remove 143 lines of particularly ugly segmentation workarounds 🙌

The remaining 1/6th of the second push provided the perfect occasion for some light TH02 PI work. The global boss position and damage variables represented some equally low-hanging fruit, being easily identified global variables that aren't part of a larger structure in this game. In an interesting twist, TH02 is the only game that uses an increasing damage value to track boss health rather than decreasing HP, and also doesn't internally distinguish between bosses and midbosses as far as these variables are concerned. Obviously, there's quite a bit of state left to be RE'd, not least because Marisa is doing her own thing with a bunch of redundant copies of her position, but that was too complex to figure out right now.

Also doing their own thing are the Five Magic Stones, which need five positions rather than a single one. Since they don't move, the game doesn't have to keep 📝 separate position variables for both VRAM pages, and can handle their positions in a much simpler way that made for a nice final commit.

And for the first time in a long while, I quite like what ZUN did there!

Not only are their positions stored in an array that is indexed with a consistent ID for every stone, but these IDs also follow the order you fight the stones in: The two inner ones use 0 and 1, the two outer ones use 2 and 3, and the one in the center uses 4. This might look like an odd choice at first because it doesn't match their horizontal order on the playfield. But then you notice that ZUN uses this property in the respective phase control functions to iterate over only the subrange of active stones, and you realize how brilliant it actually is.

This seems like a really basic thing to get excited about, especially since the rest of their data layout sure isn't perfect. Splitting each piece of state and even the individual X and Y coordinates into separate 5-element arrays is still counter-productive because the game ends up paying more memory and CPU cycles to recalculate the element offsets over and over again than this would have ever saved in cache misses on a 486. But that's a minor issue that could be fixed with a few regex replacements, not a misdesigned architecture that would require a full rewrite to clean it up. Compared to the hardcoded and bloated mess that was 📝 YuugenMagan's five eyes, this is definitely an improvement worthy of the good-code tag. The first actual one in two years, and a welcome change after the Music Room!

These three pieces of data alone yielded a whopping 5% of overall TH02 PI in just 1/6th of a push, bringing that game comfortably over the 60% PI mark. MAINE.EXE is guaranteed to reach 100% PI before I start working on the non-ASCII translations, but at this rate, it might even be realistic to go for 100% PI on MAIN.EXE as well? Or at least technical position independence, without the false positives.

Next up: Shuusou Gyoku SC-88Pro BGM. It's going to be wild.