- 📝 Posted:

- 🚚 Summary of:

- P0229, P0230, P0231, P0232, P0233, P0234

- ⌨ Commits:

6370f96...d535d87,d535d87...ca523b4,ca523b4...05a49b9,f7ef7f8...abeaf85,abeaf85...dbc5b51,dd2265c...12f29c6- 💰 Funded by:

- Ember2528, [Anonymous]

- 🏷 Tags:

128 commits! Who would have thought that the ideal first release of the TH01

Anniversary Edition would involve so much maintenance, and raise so many

research questions? It's almost as if the real work only starts after

the 100% finalization mark… Once again, I had to steal some funding from the

reserved JIS trail word pushes to cover everything I liked to research,

which means that the next towards the

anything

goal will repay this debt. Luckily, this doesn't affect any

immediate plans, as I'll be spending March with tasks that are already fully

funded.

So, how did this end up so massive? The list of things I originally set out to do was pretty short:

- Build entire game into single executable

- Fix rendering issues in the one or two most important parts of the game for a good initial impression

But even the first point already started with tons of little cleanup

commits. A part of them can definitely be blamed on the rush to hit the 100%

decompilation mark before the 25th anniversary last August.

However, all the structural changes that I can't commit to

master reveal how much of a mess the TH01 codebase actually

is.

Merging the executables is mainly difficult because of all the

inconsistencies between REIIDEN.EXE and FUUIN.EXE.

The worst parts can be found in the REYHI*.DAT format code and

the High Score menu, but the little things are just as annoying, like how

the current score is an unsigned variable in

REIIDEN.EXE, but a signed one in FUUIN.EXE.

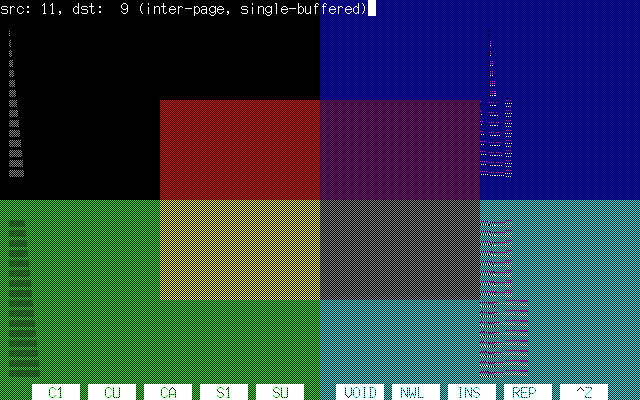

![]() If it takes me this long and this many

commits just to sort out all of these issues, it's no wonder that the only

thing I've seen being done with this codebase since TH01's 100%

decompilation was a single porting attempt that ended in a rather quick

ragequit.

If it takes me this long and this many

commits just to sort out all of these issues, it's no wonder that the only

thing I've seen being done with this codebase since TH01's 100%

decompilation was a single porting attempt that ended in a rather quick

ragequit.

So why are we merging the executables in preparation for the Anniversary

Edition, and not waiting with it until we start doing ports?

- Distributing and updating one executable is cleaner than doing the same with three, especially as long as installation will still involve manually dropping the new binary into the game directory.

- The Anniversary Edition won't be the only fork binary. We are already

going to start out with a separate

DEBLOAT.EXEthat contains only the bloat removal changes without any bug fixes, and spaztron64 will probably redo his seizure-less edition. We don't want to clutter the game directory with three binaries for each of these fork builds, and we especially don't want to remember things likeoh, but this fork only modifies

…REIIDEN.EXE - All forks should run side-by-side with the original game. During the time I was maintaining thcrap, I've had countless bug reports of people assuming that thcrap was responsible for bugs that were present in the original game, and the same is certain to happen with the Anniversary Edition. Separate binaries will make it easier for everyone to check where these bugs came from.

- Also, I'd like to make a point about how bloated the original three-executable structure really is, since I've heard people defending it as neat software architecture. Really, even in Real Mode where you typically want to use as little of the 640 KiB of conventional memory as possible, you don't want to split your game up like this.

The game actually is so bloated that the combined binary ended up

smaller than the original REIIDEN.EXE. If all you see are the

file sizes of the original three executables, this might look like a

pretty impressive feat. Like, how can we possibly get 407,812

bytes into less than 238,612 bytes, without using compression?

If you've ever looked at the linker map though, it's not at all surprising.

Excluding the aforementioned inconsistencies that are hard to quantify,

OP.EXE and FUUIN.EXE only feature 5,767 and 6,475

bytes of unique code and data, respectively. All other code in these

binaries is already part of REIIDEN.EXE, with more than half of

the size coming from the Borland C++ runtime. The single worst offender here

is the C++ exception handler that Borland forces

onto every non-.COM binary by default, which alone adds 20,512 bytes

even if your binary doesn't use C++ exceptions.

On a more hilarious note, this

single line is responsible for pulling another unnecessary 14,242 bytes

into OP.EXE and FUUIN.EXE. This floating-point

multiplication is completely unnecessary in this context because all

possible parameters are integers, but it's enough for Turbo C++ and TLINK to

pull in the entire x87 FPU emulation machinery. These two binaries don't

even draw lines, but since this function is part of the general

graphics code translation unit and contains other functions that these

binaries do need, TLINK links in the entire thing. Maybe, multiple

executables aren't the best choice either if you use a linker that can't do

dead code elimination…

Since the 📝 Orb's physics do turn the entire

precision of a double variable into gameplay effects, it's not

feasible to ever get rid of all FPU code in TH01. The exception handler,

however, can

be removed, which easily brings the combined binary below the size of

the original REIIDEN.EXE. Compiling all code with a single set

of compiler optimization flags, including the more x86-friendly

pascal calling convention, then gets us a few more KB on top.

As does, of course, removing unused code: The only remaining purpose of

features such as 📝 resident palettes is to

potentially make porting more difficult for anyone who doesn't immediately

realize that nothing in the game uses these functions.

Technically, all unused code would be bloat, but for now, I'm keeping

the parts that may tell stories about the game's development history (such

as unused effects or the 📝 mouse cursor), or

that might help with debugging. Even with that in mind, I've only scratched

the surface when it comes to bloat removal, and the binary is only going to

get smaller from here. A lot smaller.

If only we now could start MDRV98 from this new combined binary, we wouldn't need a second batch file either…

Which brings us to the first big research question of this delivery. Using

the C spawn() function works fine on this compiler, so

spawn("MDRV98.COM") would be all we need to do, right? Except

that the game crashes very soon after that subprocess returned.

![]()

So it's not going to be that easy if the spawned process is a TSR.

But why should this be a problem? Let's take a look at the DOS heap, and how

DOS lays out processes in conventional memory if we launch the game

regularly through GAME.BAT:

GAME.BAT.

The batch file starts MDRV98 first, which will therefore end up below

the game in conventional memory. This is perfect for a TSR: The program can

resize itself arbitrarily before returning to DOS, and the rest of memory

will be left over for the game. If we assume such a layout, a DOS program

can implement a custom memory allocator in a very simple way, as it only has

to search for free memory in one direction – and this is exactly how Borland

implemented the C heap for functions like malloc() and

free(), and the C++ new and delete

operators.

But if we spawn MDRV98 after starting TH01, well…

MDRV98 will spawn in the next free memory location, allocate itself, return to TH01… which suddenly finds its C heap blocked from growing. As a result, the next big allocation will immediately fail with a rather misleading "out of memory" error.

So, what can we do about this? Still in a bloat removal mindset, my gut

reaction was to just throw out Borland's C heap implementation, and replace

it with a very thin wrapper around the DOS heap as managed by INT 21h,

AH=48h/49h/4Ah. Like, why

did these DOS compilers even bother with a custom allocator in the first

place if DOS already comes with a perfectly fine native one? Using the

native allocator would completely erase the distinction between TSR memory

and game memory, and inherently allow the game to allocate beyond

MDRV98.

I did in fact implement this, and noticed even more benefits:

- While DOS uses 16 bytes rather than Borland's 4 bytes for the control

structure of each memory block, this larger size automatically aligns all

allocations to 16-byte boundaries. Therefore, all allocation addresses would

fit into 16-bit segment-only pointers rather than needing 32-bit

farones. On the Borland heap, the 4-byte header further limits regularfarpointers to 65,532 bytes, forcing you into expensivehugepointers for bigger allocations. - Debuggers in DOS emulators typically have features to show and manage the DOS heap. No need for custom debugging code.

- You can change the memory placement strategy to allocate from the top of conventional memory down to the bottom. This is how the games allocate their resident structures.

Ultimately though, the drawbacks became too significant. Most of them are

related to the PC-98 Touhou games only ever creating a single DOS

process, even though they contain multiple executables.

Switching executables is done via exec(), which resizes a

program's main allocation to match the new binary and then overwrites the

old program image with the new one. If you've ever wondered why DOSBox-X

only ever shows OP as the active process name in the title bar,

you now know why. As far as DOS is concerned, it's still the same

OP.EXE process rooted at the same segment, and

exec() doesn't bother rewriting the name either. Most

importantly though, this is how REIIDEN.EXE can launch into

another REIIDEN.EXE process even if there are less than 238,612

bytes free when exec() is called, and without consuming more

memory for every successive binary.

For now, ANNIV.EXE still re-exec()s itself at

every point where the original game did, as ZUN's original code really

depends on being reinitialized at boss and scene boundaries. The resulting

accidental semi-hot reloading

is also a useful property to retain

during development.

So why is the DOS heap a bad idea for regular game allocation after all?

- Even DOS automatically releases all memory associated with a process

during its termination. But since we keep running the same process until the

player quits out of the main menu, we lose the C heap's implicit cleanup on

exec(), and have to manually free all memory ourselves. - Since the binary can be larger after hot reloading, we in fact have

to allocate all regular memory using the last fit strategy.

Otherwise,

exec()fails to resize the program's main block for the same reason that crashed the game on our initial attempt tospawn("MDRV98.COM"). - Just like Borland's heap implementation, the DOS heap stores its control

structures immediately before each allocation, forming a singly linked list.

But since the entire OS shares this single list, corruptions from heap

overflows also affect the whole system, and become much more disastrous.

Theoretically, it might be possible to recover from them by forcibly

releasing all blocks after the last correct one, or even by doing a

brute-force search for valid memory

control blocks, but in reality, DOS will likely just throw error code #7

(

ERROR_ARENA_TRASHED) on the next memory management syscall, forcing a reboot.

With a custom allocator, small corruptions remain isolated to the process. They can be even further limited if the process adds some padding between its last internal allocation and the end of the allocated DOS memory block; Borland's heap sort of does this as well by always rounding up the DOS block to a full KiB. All this might not make a difference in today's emulated and single-tasked usage, but would have back then when software was still developed inside IDEs running on the same system. - TH01's debug mode uses

heapcheck()andheapchecknode(), and reimplementing these on top of the DOS heap is not trivial. On the contrary, it would be the most complicated part of such a wrapper, by far. - Finally, and most importantly for TH01 in particular: The observable effects of the 📝 test/debug mode HP bar heap corruption glitches are a direct result of Borland's C heap implementation.

I could release this DOS heap wrapper in unused form for another push if anyone's interested, but for now, I'm pretty happy with not actually using it in the games. Instead, let's stay with the Borland C heap, and find a way to push MDRV98 to the very top of conventional RAM. Like this:

Which is much easier said than done. It would be nice if we could just use

the last fit allocation strategy here, but .COM executables always

receive all free memory by default anyway, which eliminates any difference

between the strategies.

But we can still change memory itself. So let's temporarily claim all

remaining free memory, minus the exact amount we need for MDRV98, for our

process. Then, the only remaining free space to spawn MDRV98 is at the exact

place where we want it to be:

Now we only need to know how much memory to not temporarily allocate. First,

we need to replicate the assumption that MDRV98's -M7

command-line parameter corresponds to a resident size of 23,552 bytes. This

is not as bad as it seems, because the -M parameter explicitly

has a KiB unit, and we can nicely abstract it away for the API.

The (env.) block though? Its minimum size equals the combined length

of all environment variables passed to the process, but its maximum size is…

not limited at all?! As in, DOS implementations can add and have

historically added more free space because some programs insisted on storing

their own new environment variables in this exact segment. DOSBox and

DOSBox-X follow this tradition by providing a configuration option for the

additional amount of environment space, with the latter adding 1024

additional bytes by default, y'know, just in case someone wants to compile

FreeDOS on a slow emulator. It's not even worth sending a bug report for

this specific case, because it's only a symptom of the fact that

unexpectedly large program environment blocks can and will happen, and are

to be expected in DOS land.

So thanks to this cruel joke, it's technically impossible to achieve what we

want to do there. Hooray! The only thing we can kind of do here is an

educated guess: Sum up the length of all environment variables in our

environment block, compare that length against the allocated size of the

block, and assume that the MDRV98 process will get as much additional memory

as our process got. 🤷

The remaining hurdles came courtesy of some Borland C runtime implementation

details. You would think that the temporary reallocation could even be done

in pure C using the sbrk(), coreleft(), and

brk() functions, but all values passed to or returned from

these functions are inaccurate because they don't factor in the

aforementioned KiB padding to the underlying DOS memory block. So we have to

directly use the DOS syscalls after all. Which at least means that learning

about them wasn't completely useless…

The final issue is caused inside Borland's

spawn() implementation. The environment block for the

child process is built out of all the strings reachable from C's

environ pointer, which is what that FreeDOS build process

should have used. Coalescing them into a single buffer involves yet

another C heap allocation… and since we didn't report our DOS memory block

manipulation back to the C heap, the malloc() call might think

it needs to request more memory from DOS. This resets the DOS memory block

back to its intended level, undoing our manipulation right before the actual

INT 21h, AH=4Bh

EXEC syscall. Or in short:

Manipulate DOS heap ➜spawn()call ➜_LoadProg()➜ allocate and prepare environment block ➜_spawn()➜ DOSEXECsyscall

The obvious solution: Replace _LoadProg(), implement the

coalescing ourselves, and do it before the heap manipulation. Fortunately,

Borland's internal low-level _spawn() function is not

static, so we can call it ourselves whenever we want to:

Allocate and prepare environment block ➜ manipulate DOS heap ➜_spawn()call ➜EXECsyscall

So yes, launching MDRV98 from C can be done, but it involves advanced

witchcraft and is completely ridiculous. ![]() Launching external sound drivers from a batch file is the right way

of doing things.

Launching external sound drivers from a batch file is the right way

of doing things.

Fortunately, you don't have to rely on this auto-launching feature. You can

still launch DEBLOAT.EXE or ANNIV.EXE from a batch

file that launched MDRV98.COM before, and the binaries will

detect this case and skip the attempt of launching MDRV98 from C. It's

unlikely that my heuristic will ever break, but I definitely recommend

replicating GAME.BAT just to be completely sure – especially

for user-friendly repacks that don't want to include the original game

anyway.

This is also why ANNIV.EXE doesn't launch

ZUNSOFT.COM: The "correct" and stable way to launch

ANNIV.EXE still involves a batch file, and I would say that

expecting people to remove ZUNSOFT.COM from that file is worse

than not playing the animation. It's certainly a debate we can have, though.

This deep dive into memory allocation revealed another previously

undocumented bug in the original game. The RLE decompression code for the

東方靈異.伝 packfile contains two heap overflows, which are

actually triggered by SinGyoku's BOSS1_3.BOS and Konngara's

BOSS8_1.BOS. They only do not immediately crash the game when

loading these bosses thanks to two implementation details of Borland's C

heap. ![]()

Obviously, this is a bug we should fix, but according to the definition of

bugs, that fix would be exclusive to the anniversary branch.

Isn't that too restrictive for something this critical? This code is

guaranteed to blow up with a different heap implementation, if only in a

Debug build. ![]() And besides, nobody would notice a fix

just by looking at the game's rendered output…

And besides, nobody would notice a fix

just by looking at the game's rendered output…

Looks like we have to introduce a fourth category of weird code, in addition

to the previous bloat, bug, and quirk categories, for

invisible internal issues like these. Let's call it landmine, and fix

them on the debloated branch as well. Thanks to

Clerish for the naming inspiration!

With this new category, the full definitions for all categories have become

quite extensive. Thus, they now live in CONTRIBUTING.md

inside the ReC98 repository.

With the new discoveries and the new landmine category, TH01 is now at 67 bugs and 20 landmines. And the solution for the landmine in question? Simplifying the 61 lines of the original code down to 16. And yes, I'm including comments in these numbers – if the interactions of the code are complex enough to require multi-paragraph comments, these are a necessary and valid part of the code.

While we're on the topic of weird code and its visible or invisible effects,

there's one thing you might be concerned about. With all the rearchitecting

and data shifting we're doing on the debloated branch, what

will happen to the 📝 negative glitch stages?

These are the result of a clearly observable bug that, by definition, must

not be fixed on the debloated branch. But given that the

observable layout of the glitch stages is defined by the memory

surrounding the scene stage variable, won't the

debloated branch inherently alter their appearance (= ⚠️

fanfiction ⚠️), or even remove them completely?

Well, yes, it will. But we can still preserve their layout by

hardcoding

the exact original data that the game would originally read, and even emulate

the original segment relocations and other pieces of global data.

Doing this is feasible thanks to the fact that there are only 4 glitch

stages. Unfortunately, the same can't be said for the timer values, which

are determined by an array lookup with the un-modulo'd stage ID. If we

wanted to preserve those as well, we'd have to bundle an exact copy of the

original REIIDEN.EXE data segment to preserve the values of all

32,768 negative stages you could possibly enter, together with a map

of all relocations in this segment. 😵 Which I've decided against for now,

since this has been going on for far too long already. Let's first see if

anyone ever actually complains about details like this…

Alright, time to start the anniversary branch by rendering

everything at its correct internal unaligned X position? Eh… maybe not quite

yet. If we just hacked all the necessary bit-shifting code into all the

format-specific blitting functions, we'd still retain all this largely

redundant, bad, and slow code, and would make no progress in terms of

portability. It'd be much better to first write a single generic blitter

that's decently optimized, but supports all kinds of sprites to make this

optimization actually worth something.

So, next research question: How would such a blitter look like? After I

learned during my

📝 first foray into cycle counting that port

I/O is slow on 486 CPUs, it became clear that TH04's

📝 GRCG batching for pellets was one of the

more useful optimizations that probably contributed a big deal towards

achieving the high bullet counts of that game. This leads to two

conclusions:

- master.lib's

super_*()sprite functions are slow, and not worth looking at for inspiration. Even the 📝 tiny format reinitializes the GRCG on every color change, wasting 80 cycles. - Hence, our low-level blitting API should not even care about colors. It should only concern itself with blitting a given 1bpp sprite to a single VRAM segment. This way, it can work for both 4-plane sprites and single-plane sprites, and just assume that the GRCG is active.

Maybe we should also start by not even doing these unaligned bit shifts ourselves, and instead expect the call site to 📝 always deliver a byte-aligned sprite that is correctly preshifted, if necessary? Some day, we definitely should measure how slow runtime shifting would really be…

What we should do, however, are some further general optimizations that I

would have expected from master.lib: Unrolling the vertical

loop, and baking a single function for every sprite width to eliminate

the horizontal loop. We can then use the widest possible x86

MOV instruction for the lowest possible number of cycles per

row – for example, we'd blit a 56-wide sprite with three MOVs

(32-bit + 16-bit + 8-bit), and a 64-wide one with two 32-bit

MOVs.

Or maybe not? There's a lot of blitting code in both master.lib and PC-98

Touhou that checks for empty bytes within sprites to skip needlessly writing

them to VRAM:

uint8_t left_half = ((uint8_t *)(sprite))[0];

uint8_t right_half = ((uint8_t *)(sprite))[1];

if(right_half != 0x00) {

pokeb(VRAM_SEGMENT, (vram_offset + 0), left_half);

}

if(right_half != 0x00) {

pokeb(VRAM_SEGMENT, (vram_offset + 1), right_half);

}Which goes against everything you seem to know about computers. We aren't running on an 8-bit CPU here, so wouldn't it be faster to always write both halves of a sprite in a single operation?

uint16_t both_halves = ((uint16_t *)(sprite))[0]; pokew(VRAM_SEGMENT, vram_offset, both_halves);

That's a single CPU instruction, compared to two instructions and two branches. The only possible explanation for this would be that VRAM writes are so slow on PC-98 that you'd want to avoid them at all costs, even if that means additional branching on the CPU to do so. Or maybe that was something you would want to do on certain models with slow VRAM, but not on others?

So I wrote a benchmark to answer all these questions, and to compare my new blitter against typical TH01 blitting code:

2023-03-05-blitperf.zip And here are the real-hardware results I've got from the PC-9800 Central Discord server:

| PC-286LS | PC-9801ES | PC-9821Cb/Cx | PC-9821Ap3 | PC-9821An | PC-9821Nw133 | PC-9821Ra20 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80286, 12 MHz | i386SX, 16 MHz | 486SX, 33 MHz | 486DX4, 100 MHz | Pentium, 90 MHz | Pentium, 133 MHz | Pentium Pro, 200 MHz | ||||||||||

| 1987 | 1989 | 1994 | 1994 | 1994 | 1997 | 1996 | ||||||||||

| Unchecked | C | GRCG | 36,85 | 38,42 | 26,02 | 26,87 | 3,98 | 4,13 | 2,08 | 2,16 | 1,81 | 1,87 | 0,86 | 0,89 | 1,25 | 1,25 |

MOVS |

GRCG | 15,22 | 16,87 | 9,33 | 10,19 | 1,22 | 1,37 | 0,44 | 0,44 | |||||||

MOV |

GRCG | 15,42 | 17,08 | 9,65 | 10,53 | 1,15 | 1,3 | 0,44 | 0,44 | |||||||

| 4-plane | 37,23 | 43,97 | 29,2 | 32,96 | 4,44 | 5,01 | 4,39 | 4,67 | 5,11 | 5,32 | 5,61 | 5,74 | 6,63 | 6,64 | ||

| Checking first | GRCG | 17,49 | 19,15 | 10,84 | 11,72 | 1,27 | 1,44 | 1,04 | 1,07 | 0,54 | 0,54 | |||||

| 4-plane | 46,49 | 53,36 | 35,01 | 38,79 | 5,66 | 6,26 | 5,43 | 5,74 | 6,56 | 6,8 | 8,08 | 8,29 | 10,25 | 10,29 | ||

| Checking second | GRCG | 16,47 | 18,12 | 10,77 | 11,65 | 1,25 | 1,39 | 1,02 | 0,51 | 0,51 | ||||||

| 4-plane | 43,41 | 50,26 | 33,79 | 37,82 | 5,22 | 5,81 | 5,14 | 5,43 | 6,18 | 6,4 | 7,57 | 7,77 | 9,58 | 9,62 | ||

| Checking both | GRCG | 16,14 | 18,03 | 10,84 | 11,71 | 1,33 | 1,49 | 1,01 | 0,49 | 0,49 | ||||||

| 4-plane | 43,61 | 50,45 | 34,11 | 37,87 | 5,39 | 5,99 | 4,92 | 5,23 | 5,88 | 6,11 | 7,19 | 7,43 | 9,1 | 9,13 | ||

The key takeaways:

- Checking for empty bytes has never been a good idea.

- Preshifting sprites made a slight difference on the 286. Starting with

the 386 though, that difference got smaller and smaller, until it completely

vanished on Pentium models. The memory tradeoff is especially not worth it

for 4-plane sprites, given that you would have to preshift each of the 4

planes and possibly even a fifth alpha plane. Ironically, ZUN only ever

preshifted monochrome single-bitplane sprites with a width of 8 pixels.

That's the smallest possible amount of memory a sprite can possibly take,

and where preshifting consequently has the smallest effect on performance.

Shifting 8-wide sprites on the fly literally takes a single

ROLorRORinstruction per row. - You might want to use

MOVSinstead ofMOVwhen targeting the 286 and 386, but the performance gains are barely worth the resulting mess you would make out of your blitting code. On Pentium models, there is no difference. - Use the GRCG whenever you have to render lots of things that share a static 8×1 pattern.

- These are the PC-98 models that the people who are willing to test your newly written PC-98 code actually use.

Since this won't be the only piece of game-independent and explicitly

PC-98-specific custom code involved in this delivery, it makes sense to

start a

dedicated PC-98 platform layer. This code will gradually eliminate the

dependency on master.lib and replace it with better optimized and more

readable C++ code. The blitting benchmark, for example, is already

implemented completely without master.lib.

While this platform layer is mainly written to generate optimal code within

Turbo C++ 4.0J, it can also serve as general PC-98 documentation for

everyone who prefers code over machine-translating old Japanese books. Not

to mention the immediacy of having all actual relevant information in

one place, which might otherwise be pretty well hidden in these books, or

some obscure old text file. For example, did you know that uploading gaiji

via INT 18h might end up disabling the VSync interrupt trigger,

deadlocking the process on the next frame delay loop? This nuisance is not

replicated by any emulators, and it's quite frustrating to encounter it when

trying to run your code on real hardware. master.lib works around it by

simply hooking INT 18h and unconditionally reenabling the VSync

interrupt trigger after the original handler returns, and so does our

platform layer.

So, with the pellet draw calls batched and routed through the new renderer, we should have gained enough free CPU cycles to disable 📝 interlaced pellet rendering without any impact on frame rates?

Well, kinda. We do get 56.4 FPS, but only together with noticeable and

reproducible tearing in the top part of the playfield, suggesting exactly

why ZUN interlaced the rendering in the first place. 😕 So have we

already reached the limit of single-buffered PC-98 games here, or can we

still do something about it?

As it turns out, the main bottleneck actually lies in the pellet

unblitting code. Every EGC-"accelerated" unblitting call in TH01 is

as unbatched as the pellet blitting calls were, spending an additional 17

I/O port writes per call to completely set up and shut down the EGC, every

time. And since this is TH01, the two-instruction operation of changing the

active PC-98 VRAM page isn't inlined either, but instead done via a function

call to a faraway segment. On the 486, that's:

- >341 cycles for EGC setup and teardown, plus

- >72 cycles for each 16-pixel chunk to be unblitted.

This sums up to

- >917 cycles of completely unnecessary work for every active pellet, in the optimal 50% of cases where it lies on an even VRAM byte, or

- >1493 cycles if it lies on an odd VRAM byte, because ZUN's code

extends the unblitted rectangle to a gargantuan 32×8 pixels in this case

And this calculation even ignores the lack of small micro-optimizations that could further optimize the blitting loop. Multiply that by the game's pellet cap of 100, and we get a 6-digit number of wasted CPU cycles. On paper, that's roughly 1/6 of the time we have for each of our target 56.423 FPS on the game's target 33 MHz systems. Might not sound all too critical, but the single-buffered nature of the game means that we're effectively racing the beam on every frame. In turn, we have to be even more serious about performance.

So, time to also add a batched EGC API to our PC-98 platform layer? Writing

our own EGC code presents a nice opportunity to finally look deeper into all

its registers and configuration options, and see what exactly we can do

about ZUN's enforced 16-pixel alignment.

To nobody's surprise, this alignment is completely unnecessary, and only

displays a lack of knowledge about the chip. While it is true that

the EGC wants VRAM to be exclusively addressed in 16-bit chunks at

16-bit-aligned addresses, it specifically provides

- an address register (

0x4AC) for shifting the horizontal start offsets of the source and destination to any pixel within the 16 pixels of such a chunk, and - a bit length register (

0x4AE) for specifying the total width of pixels to be transferred, which also implies the correct end offsets.

And it gets even better: After ⌈bitlength ÷ 16⌉ write

instructions, the EGC's internal shifter state automatically reinitializes

itself in preparation for blitting another row of pixels with the same

initially configured bit addresses and length. This is perfect for blitting

rectangles, as two I/O port writes before the start of your blitting loop

are enough to define your entire rectangle.

The manual nature of reading and writing in 16-pixel chunks does come with a

slight pitfall though. If the source bit address is larger than the

destination bit address, the first 16-bit read won't fill the EGC's internal

shift register with all pixels that should appear in the first 16-pixel

destination chunk. In this case, the EGC simply won't write anything and

leave the first chunk unchanged. In a

📝 regular blitting loop, however, you expect

that memory to be written and immediately move on to the next chunks within

the row. As a result, the actual blitting process for such a rectangle will

no longer be aligned to the configured address and bit length. The first row

of the rectangle will appear 16 pixels to the right of the destination

address, and the second one will start at bit offset 0 with pixels from the

rightmost byte of the first line, which weren't blitted and remained in the

tile register.

There is an easy solution though: Before the horizontal loop on each line of

the rectangle, simply read one additional 16-pixel chunk from the source

location to prefill the shift register. Thankfully, it's large enough to

also fit the second read of the then full 16 pixels, without dropping any

pixels along the way.

And that's how we get arbitrarily unaligned rectangle copies with the EGC! Except for a small register allocation trick to use two-register addressing, there's not much use in further optimizations, as the runtime of these inter-page blit operations is dominated by the VRAM page switches anyway.

Except that T98-Next seems to disagree about the register prefilling issue:

Every other emulator agrees with real hardware in this regard, so we can

safely assume this to be a bug in T98-Next. Just in case this old emulator

with its last release from June 2010 still has any fans left nowadays… For

now though, even they can still enjoy the TH01 Anniversary Edition: The only

EGC copy algorithm that TH01 actually needs is the left one during the

single-buffered tests, which even that emulator gets right.

That only leaves

📝 my old offer of documenting the EGC raster ops,

and we've got the EGC figured out completely!

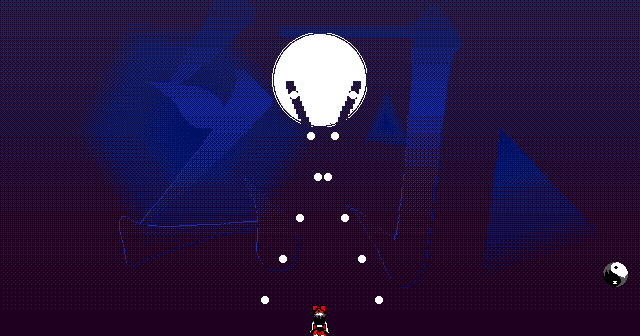

And that did in fact remove tearing from the pellet rendering function! For the first time, we can now fight Elis, Kikuri, Sariel, and Konngara with a doubled pellet frame rate:

coreleft)…

With only pellets and no other animation on screen, this exact pattern

presents the optimal demonstration case for the new unblitter. But as you

can already tell from the invincibility sprites, we'd also need to route

every other kind of sprite through the same new code. This isn't all too

trivial: Most sprites are still rendered at byte-aligned positions, and

their blitting APIs hide that fact by taking a pixel position regardless.

This is why we can't just replace ZUN's original 16-pixel-aligned EGC

unblitting function with ours, and always have to replace both the blitter

and the unblitter on a per-sprite basis.

To completely remove all flickering, we'd also like to get rid of all the

sprite-specific unblit ➜ update ➜ render sequences, and instead

gather all unblitting code to the beginning of the game loop, before any

update and rendering calls. So yeah, it will take a long time to completely

get rid of all flickering. Until we're there, I recommend any backer to tell

me their favorite boss, so that I can focus on getting that one

rendered without any flickering. Remember that here at ReC98, we can have a

Touhou character popularity contest at any time during the year, whenever

the store is open! ![]()

In the meantime, the consistent use of 8×8 rectangles during pellet unblitting does significantly reduce flickering across the entire game, and shrinks certain holes that pellets tend to rip into lazily reblitted sprites:

To round out the first release, I added all the other bug fixes to achieve

parity with my previously released patched REIIDEN.EXE builds:

- I removed the 📝 shootout laser crash by simply leaving the lasers on screen if a boss is defeated,

- prevented the HP bar heap corruption bug in test or debug mode by not letting it display negative HP in the first place, and

- restored 📝 the two animations during the Sariel fight that were lost to type confusion errors in the original game.

So here it is, the first build of TH01's Anniversary Edition: 2023-03-05-th01-anniv.zip Edit (2023-03-12): If you're playing on Neko Project and seeing more flickering than in the original game, make sure you've checked the Screen → Disp vsync option.

Next up: The long overdue extended trip through the depths of TH02's low-level code. From what I've seen of it so far, the work on this project is finally going to become a bit more relaxing. Which is quite welcome after, what, 6 months of stressful research-heavy work?